13

The Hollywood Reporter

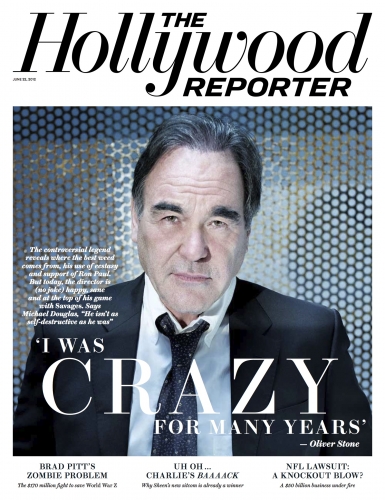

Less Crazy After All These Years - The Hollywood Reporter

Yes, Oliver Stone will tell you about losing his virginity to a call girl, smoking grass, doing ecstasy and everything about his colorful life in between. But nowadays, Savages’ controversial

Tdirector is mellower, happier and has nothing to hide: “i’m not a Prozac person anymore” by Stephen Galloway photographed by Kurt ISwarIenKo

The first time I met oliver stone, he tried to pick up my girlfriend. It was nearly 20 years ago, and she’d stuck her head into his Natural Born Killers editing room; he promised her a role in his next film. He didn’t seem bothered that there was no role, much less that she had a boyfriend.

By then, the hard-living director of films such as Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July and Wall Street infamously had had his first sexual experience with a call girl (procured by his father); done a stint in Vietnam; frequented hordes of women in Saigon (paid and unpaid); been thrown in a Mexican jail for marijuana posses- sion then been arrested again in Los Angeles in 2005; incensed the entire Turkish population for his portrayal of its prisons in Midnight Express; and spent years in a drug-induced haze.

His reputation as the baddest of Hollywood bad boys dwarfed even that of his closest rival, Top Gun producer Don Simpson, who reportedly died while sitting on a toilet reading a Stone biography.

Nearly two decades have passed since the now-65-year-old filmmaker reached his nadir; still, it is with some trepidation that I approach his West Los Angeles offices for lunch May 10. After I wait a while near a painting of Che Guevara and an artwork inspired by Jimi Hendrix’s death certificate, Stone lopes in, casually dressed in a blue jacket and jeans, his black hair thinning, but as charismatic as any movie star. He’s grinning from ear to ear, warm and welcoming and nothing like the dark figure of lore.

“Jesus, you’re early!” he exclaims in mock protest. (He’s notorious for being late.) Then he pulls up a chair at an unpretentious table in his office, littered with books and scripts, and we munch on sandwiches.

“I was crazy for many years,” he admits. “So is everybody, you know. But now, I’m pretty sane. There’s been so much craziness in my life — and there still is — but it gets out through the work.”

Perhaps getting older has mellowed him. Perhaps it’s the daily meditation he practices. Or perhaps it’s his third marriage, to Chong Stone, 57, a South Korean immigrant he met when she was working at a New York restaurant.

“She came from a very poor background,” says Stone. “She had an arranged marriage. She didn’t see a car until she was 15, she didn’t see a television. She was one of six or seven children. Her mother brought her out of school so that she would help with the house; she was the oldest sister. She grew up in another world, you have to understand — it’s just a different tonality: the culture, the way they speak, the way they listen. She’s the opposite of everything I am. She flows with the East. I go back and see her face, and it’s very calm. She comes from another place of graciousness, transparency, selflessness. That’s why I love her.”

Stone says his wife had been thinking of returning to Korea when they met: “We were gonna break up — I told her I didn’t want to get married because I’d been married and it wasn’t working for me, and the only reason I’d marry is to have a kid. I swear to God, she just said, ‘Yes, that would be wonderful.’ And she comes back six weeks later and says, ‘I’m pregnant.’ It was unbelievable.”

The couple has a 16-year-old daughter, Tara, Stone’s third child after two boys, who has turned the once-wild patriarch into a domestic disci- plinarian. “I’m the tough guy now,” he smiles. “Sometimes I gotta crack the whip.” Thanks to all this — the wife, the meditation, the child — Stone is very different today from the crash-and-burn figure of the 1990s.

Sure, he likes to party. But when he’s not working, he mostly spends time at his “Tudor/ Chinese” home in L.A.’s Mandeville Canyon (he also has apartments in Manhattan and Beijing); reads history books (among them Alistair Horne’s The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 and Seymour Topping’s The Peking Letter: A Novel of the Chinese Civil War); watches TV series from Mad Men to Homeland to The Daily Show With Jon Stewart; and keeps up with movies as diverse as Snow White and the Huntsman and Argentina’s Oscar-winning The Secret in Their Eyes — both of which he unabashedly enjoyed.

Yet controversy sticks to him like glue. “The controversies hurt,” he says ruefully. “People thought I was going after them, but they don’t help the movies.” Still, Stone does little to diminish their root cause, his reputation as a conspiracy nut. “There are so many conspiracies in history, it is ridiculous to defend yourself on those lines,” he says.

His oldest child, Sean, 27, a documentary filmmaker (one of two sons with his second wife), recently converted to Islam and changed his name to Ali. Stone isn’t fazed. “He decided for himself, and he is doing it for philosophical purposes,” he shrugs. “At that age, I did a lot crazier things.”

Then there’s his protege Charlie Sheen’s outlandish behavior. “Oh boy, you’re going to get me in trouble,” groans Stone, jokingly bury-

ing his face in his hands and noting the two are not close; indeed, the only time they’ve gotten together in years was at a recent THR photo shoot. “Fame did it to him, not me. He got wild. Listen, he’s one of the richest actors in the world. He wanted money. He loved money. Maybe he was more like the Wall Street boy than we knew.”

He’s less amused by Richard Dreyfuss, who played Dick Cheney in Stone’s 2008 biopic W and lambasted his director as a “fascist.” “That was probably the single worst experience I’ve ever had with an actor in my life,” the helmer shoots back, saying Dreyfuss couldn’t remember his lines. “I walked him outside, and I read him the Riot Act. I said, ‘You’re going to read these f—ing cue cards, and if you don’t read them, this scene is over.’ So, yeah, I was a fascist.” Beyond Dreyfuss, the filmmaker inflamed much of Hollywood in 2010 when he complained of Jewish “domination” of the media and u.S. foreign policy. “I apologized for it,” he notes, adding he is half-Jewish on his father’s side. “I meant that the state of Israel and its policy have a very undue influence on American media.”

Lately, Stone also has raised eyebrows by declaring support for right-wing Congressman Ron Paul’s presidential bid: “I like Ron Paul’s magnetism, his decency, his honor and his foreign policy,” he argues. “Obama’s doing his best. He’s got his problems, and I think he made certain promises he hasn’t kept.” He remains undecided about whether to vote for the president because “Obama has carried on the Bush war on terror and has not addressed all the things he promised he would do to curtail the hype and fear that per- vade this country.” Still, he says, “It’s hard for me to vote Republican.” As for Mitt Romney, “I’m not going to vote for that idiot.”

By contrast, Stone is surprisingly restrained about the most maligned of media moguls, Rupert Murdoch: “He’s very personable, charm- ing. I don’t think he has all the facts sometimes. But he’s a battler. He’s one of the only big news guys I know who has fun.”

So does Stone these days — if admittedly helped by the occasional illicit substance. “I’m like Willie Nelson,” he says, eyes twinkling. “I believe the grass is God’s gift. California makes the best in the world now. When I was a kid, it was Vietnamese,

it was Thai, Jamaican for a while. All my life I’ve been doing it, off and on. I can stop marijuana. I can [go without it] for weeks and weeks. I’m not addicted, but I enjoy it. I also enjoy alcohol.”

As for heavy drugs: “Cocaine, I stay away from. But I believe in LSD, mescaline, mushrooms, ayahuasca. You ever heard of ayahuasca? It’s a very strong juice that comes from the rubber trees. Ecstasy is great, too.”

Then he looks at me, amused. “I bet you didn’t ask Ridley this stuff,” he says, referring to a recent profile on Prometheus director Ridley Scott by this same writer. When I assure him Scott got his share of tough questions, he laughs gleefully.

“God, you’re insane!”

Stone, despite his reputation, is not. Although he has ruffled some colleagues — possibly including longtime cinematographer Robert Richardson, with whom he “had a divorce, and like all divorces, it was painful” — he’s got his feet firmly planted on the ground when it comes to playing the Hollywood game. He knows how to bring a movie in on time and even under budget, as he did universal’s mid- $40 million drug drama Savages.

The film — about two pot growers whose mutual girlfriend is kidnapped by a Mexican cartel — stars Taylor Kitsch, Blake Lively, Aaron Johnson, Benicio Del Toro, Salma Hayek and John Travolta. It’s getting the type of buzz that leads insiders to believe Stone — arguably one of Hollywood’s most original filmmakers and inarguably its most compelling personality — is back at his best. “This movie reminds us that Oliver, when he’s working in his milieu, is one of the great direc- tors of his generation,” says universal Pictures co-chairman Donna Langley, whose studio is so confident in the film that it moved its release from Sept. 28 to July 6. “He’s been amazing to work with, exceptionally collaborative and sharp and intelligent, with a healthy dose of neurotic insecurity.”

Stone first thought of making the movie in late 2010 when his CAA agent, Bryan Lourd, sent him a copy of the new Don Winslow novel.

“It was something I hadn’t done in a long time: It was contemporary, in that sort of go-for-the- ride, have-fun mode,” says the director. “After doing W and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps and World Trade Center, this was like a breath of fresh air.” Stone optioned the book with $50,000 of his own money, then started to research its subject while working on the adaptation with Winslow and Shane Salerno. “We visited several ‘grow’ houses in Southern California,” he says of his team. “We went to low-budget ones, medium- budget ones and very-high-end ones, visited some beautiful farms.”

Further research took him to Mexico, where he met with a putative drug lord. “We were housed in a beautiful ranch,” he says. “Our host puts down on the table a bottle of tequila for lunch. Serves us. It goes down smooth. And he says, ‘If I sold this, it would be $5,000 a bottle.’ I’m not a great drinker, but we drank five, 10 bottles, and I was walking straight all afternoon.” Afterward, the proprietor showed Stone how the tequila was made and some of the ingredients that went into it, including “bulls’ penises, snakes, tarantulas, bats — all was mixed in.” Getting Savages made meant Stone had to take a relatively modest $3 million to $4 million. He also had to face losing his leading lady, Jennifer Lawrence, because of her commitment to The Hunger Games. Then he had a complicated 58-day shoot that took place almost entirely in California, along with a few days in Indonesia.

“We had tight actor schedules,” notes Stone. “Blake was still shooting Gossip Girl. Travolta had other commitments. And Aaron had to start another movie. It was hard.”

Despite that, Kitsch says they rehearsed from 9 to 5 every day for two weeks in Los Angeles, helped by his military training for another universal venture. “I’d worked with Navy SEALs on Battleship,” he recalls, adding he suggested that his character, a vet, be covered with scars. “Other directors would have been, ‘No, I want you to look good!’ ” he says. To his surprise, Stone agreed without hesitation.

While Kitsch notes his director has “zero filter” in giving his opinion, he was thrilled when Stone e-mailed him after the Battleship fiasco, writing: “With any job there is always going to be self-doubt that creeps in, but know that you are going to have a long career.”

Not that this kindness — a hint of the inner Stone that has endeared him to longtime col- laborators and is often ignored by his critics — meant the Stone of old had entirely vanished.

“God knows he’s a humanitarian, but he has a dark side,” says Michael Douglas, an Oscar win- ner for Wall Street who again collaborated with him on its sequel. “He isn’t as tormented and self-destructive as he was 20 years ago, but the talent is all there.”

Adds Lively: “He’s definitely not a person who is going to hold up scorecards and cheer you

on. It’s like having a very silent, stoic father and wanting to crack him. But there wasn’t a night when he wasn’t with us or working.”

Location shoots in Laguna Beach, Malibu and various canyons northeast of Los Angeles went smoothly until the temperatures proved over- powering. “It was so hot in those canyons; the heat was like 95,” recalls Stone. “The humidity was throttling. People started to pass out.”

Stone caused something of a stir when he wanted to plant genuine marijuana (as THR reported May 3). “In a perfect world,” he would have done it, he acknowledges, because the plants have a specific look that was difficult to reproduce: “If you know high-level marijuana, it’s beautiful. But we couldn’t even get close to that because the universal legal team could not be involved in any way. The ‘grow’ houses had to be created out of synthetics. And we never had any real marijuana on the set that I know of.”

The marijuana incident was a brief echo of the larger-than-life character whose exploits were once Hollywood legend. “The crazy days are over completely,” says Savages producer Moritz Borman. “That doesn’t mean he isn’t ferocious and full of energy and creativity. But the crazy stuff that all of us were into 20 years ago, that’s gone.”

Stone got to know crazy people before he was even born. His father, Louis, had fallen in love with a young Frenchwoman, Jacqueline Goddet, while serving as an officer in France at the end of World War II, then persuaded her to follow him to America. The 35-year-old stockbroker and the 24-year-old

free spirit had an uneasy relationship, Stone reflects when we meet again two weeks after our initial interview. (He spent much of his youth in France and speaks French fluently, if tinged with an American accent.)

“They’re both strong people,” he says of his father, who died in 1985, and his mother, now 91. “My father was a serious man, a hardworking man, a Republican — not only at the highest end of the stock broking business but also a hell of a good writer. He wrote a monthly letter that was translated into 15 languages and was very respected on the Street.”

As for his mother, she “was a classic Auntie Mame type — very popular, center of attention, exaggerating everything, sleeping late in the morning, not exactly a great example. We’ve always had conflict. She was a rebel all her life; she had tons of friends and drugs and gay boys and was certainly on the wild side. It’s in me, too. I mean, a lot of her is in me, and some of that I don’t approve of.”

He rejects allegations of an incestuous relationship, hinted at in his autobiographical novel, A Child’s Night Dream. Did anything of the kind ever happen? “No,” he says categorically, though he notes parallels between his own life and the “edge of incest” in 2004’s Alexander.

Stone grew up privileged in a Manhattan townhouse but during his teens was sent away to a rigid boarding school, The Hill, and it was there at age 15 that he learned his parents were divorcing. The news proved devastating, not only because his mother subsequently disappeared for weeks but also because it coincided with his father’s financial losses, meaning Stone now lost the only home he had known.

Neither parent was faithful, and Louis at times resorted to call girls, which was how Oliver was initiated to sex. “I have no shame about it,” he reflects. “It was great. It was an exciting, wonderful experience. It was impossible [to have sex] at that time. I mean, I grew up in boarding schools. Every other kid I knew in my classes had to go to some professional for this. It wasn’t doable with women of our generation.”

He adds of his father: “I loved him. I really did. He had a wild side, too, a very wild side. He was insane on a certain level, which I loved in a way.”

Still, the marital collapse plunged Stone into despair: “I was lost for a long time, and I stayed lost. It took another 13, 14 years to start to come out of it.” Even in the decades since, he has had bouts of depression, he says. “I’ve taken medication, but it doesn’t work for me. I’m not a Prozac person anymore; I’ve already taken too much of that. I feel you have to confront it on a spiritual basis.”

Adrift and feeling as confined when he entered Yale as he had been at The Hill, Stone abandoned college to teach in Saigon and Cholon, Vietnam, before a stint in the merchant marine. “I saw this advertisement on a billboard: ‘Do you want to teach school in Cholon?’ And as long as you could get there, they’d hire you,” he explains. It was in Asia that Stone came alive: “Oh man, I’d never seen women like that in my life. Sex wasn’t evil. It wasn’t a sin. It was like eating rice. It was like a candy store. But there’s a downside, too: You can get crazy.”

The craziness might have contributed to his divorces — from Najwa Sarkis, whom he married in 1971 (they parted in 1977), and Elizabeth Cox (1981 to 1993). “I was wild,” he says. “Women were certainly a preoccupation that took a lot of my time and sometimes were a waste of money, too.”

In Vietnam, the joy of sex and Stone’s burgeoning love for Asia led him to extend his initial teaching commitment from June 1965 into the following year. When he returned to Yale and experienced a hard-hitting failure after his 1,400-page novel went unpublished, he contemplated heading back to the brave new world he’d encountered. “I wanted to get away for adventure,” he explains. “Jack London, I loved him. Hemingway, Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim” (about a young man who commits an act of cowardice) all contrib- uted to his enlisting in the Army. “Would I be a coward?” he pondered. “I was alone. Rejected. So I decided, if I go out there as an infantry soldier, it’ll sort things out for me. I was suicidal. This was a way to take it out of my hands and not make a choice.”

The young Stone — at the time using his given name, Bill — enlisted with the infantry in 1967 and remained 15 months. He acknowledges that terrible things happened. “I was a romantic. But when I got there, it became another story because it’s pretty gritty. It’s very hard, and death is very ugly. I got more realistic, I guess.” He continues: “I saw my share of ugly. You gotta kill and make sure your buddies survive. There is a line, and people lose that line over there. But I did not, nor did a lot of people I know.”

While in Vietnam, he started to take photographs, which in turn led him to film. A favorite early memory had been of trips to the movies with his mother and in particular one picture with “two lovers who were kissing in the car and crashed. The road was blocked, and they went right into it and died. It was very sad.”

Returning to the U.S., he signed up for film school at New York university, where Martin Scorsese was an influential teacher. But the following years were a struggle. In his 20s, he wrote 11 screenplays that didn’t sell or made him next to nothing (including Platoon and Fourth of July) and barely eked out a living until his career shifted gears when he was commissioned to adapt Billy Hayes’ memoir of life in a Turkish prison, Midnight Express — a movie that led to condemnation from Amnesty International, among others.

“I said in Turkey, ‘I regret there has been a misunderstanding about it,’” Stone emphasizes, noting that cuts darkened the tone of the film. “It was trimmed to make a $3.8 million movie. It was very good, but it doesn’t convey completely the absurdity of the situation in the jails and some of the humor [in the script].”

He still smarts that director Alan Parker and producer David Puttnam refused to invite him to Midnight’s Cannes premiere, but the movie won Stone a 1978 Oscar for best adapted screenplay and gave him a chance to direct his first Hollywood feature, the generally panned horror flick The Hand (1981).

Stone’s directorial hopes seemed dashed. He continued to work as a writer, but it was not until he met a flamboyant mogul named John Daly that he got his next break behind the camera.

The acclaim generated by their 1986 movie Salvador, about a down-and-out journalist (James Woods) who travels to El Salvador with his oddball buddy (James Belushi) on a mission to expose its horrors, helped him get another dream project off the ground: 1986’s Platoon.

“It was around for several years; everybody read it. And I felt like we’d never get it made, and I forgot about it and moved on with my life,” says Stone. Then Daly stepped in, along with producer Arnold Kopelson. “We made it for not more than $4 million to $5 million. During the shoot, we had a coup d’etat when Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos was kicked out. It was just tough — 50 days of rain, and we had to shoot, no matter what. But it was the right thing at the right time.”

Platoon won oscars for best picture and director. Stone also would receive an Academy Award for directing 1989’s Fourth of July, giving him three statuettes. (He has received 11 nominations in all.) Those films, along with Wall Street (1987) and JFK (1991), put him firmly in the pantheon of America’s greatest living directors — a standing that somewhat declined in the years following Natural Born Killers (1994) and was damaged in the 2000s with the critical drubbing of W and, especially, Alexander.

“Alexander is as close to me as any movie I’ve ever made because you’ll see my dad and mom there,” he says of the picture, which stars Colin Farrell as Alexander the Great. “There’s a fever to it. Alexander was true to the way I see things: the mother on the edge of incest, the mother’s hatred of the father. But it took me three years to solve that movie [in the editing], and I suffered greatly. I mean, I lost my reputation.”

Now, his colleagues say, his reputation will return with Savages. Certainly, the talent behind it is in full flow when he invites me to watch him at work on the sound mix. In a large, dark screening room at Todd-AO’s Los Angeles facility, he pores over a few minutes with a half-dozen longtime aides, chopping, changing, choosing one piece of music then replacing it with another, even in these final days of postproduction — a process similar to his filmmaking where he’s constantly rewriting and editing even as he shoots. The film moves at a frenetic pace, layering in black and white and color, mixing quick cuts and long takes, creating an almost impossibly rich texture that somehow never loses its grip on the narrative. It gives the impression of a creator at the height of his powers.

“I’ve done four films with Oliver, and he is very intense and concentrated,” says Borman. “He shoots all day, then instead of going home, he goes to the editing room and rewrites. He’s always thinking and rethinking.”

Despite that, following JFK Stone entered a more fallow period at the box office, especially with the colossal flop of his third Vietnam-centric film, 1993’s Heaven & Earth, about a country girl who marries a G.I. (Tommy Lee Jones) and follows him to America.

He’s had some critical and box-office hits since — including 2006’s World Trade Center and the 2010 Wall Street sequel — and a few disappointments, such as W, Nixon (1995) and U Turn (1997). And then there were the projects, like one centering on Martin Luther King Jr., that came close to being made, only to evaporate.

Stone took the 2007 collapse of Pinkville, about the My Lai massacre (its title refers to the Army’s name for a village thought to be communist), particularly hard.

Bruce Willis initially was attached to star, then withdrew. Late in the game, “I got Nic Cage to step in,” says Stone. “We had whole villages built in Thailand, but the hedge fund and (united Artists’) Paula Wagner pulled out. They got scared; they were worried shitless about the Iraq War.” He pauses. “They take a lot of blood out of you, the Pinkvilles and the Kings. That hurts, the stuff that doesn’t get made.”

Many artists would be crushed by such defeats, but not Stone, who has even invested his own money in an upcoming documentary series (see sidebar).

“It’s a cruel, cruel world,” he reflects with a momentary sadness. “You can’t avoid the coldness and the cruelty of it. I was born warm and couldn’t handle that. But now I’m older; I realize it’s nature. I want to find the beauty in it. If I can make poetry, it makes it all tolerable.”